Fatal Drug Overdoses Decline

Area Outreach, Naloxone, Cited For Drop In Deaths

- Capt. Robert Samuelson of the Jamestown Police Department holds a naloxone unit. The drug is likely one reason why the number of fatal drug overdoses have dropped so far this year in Chautauqua County. P-J photo by Eric Tichy

- P-J file photo

Capt. Robert Samuelson of the Jamestown Police Department holds a naloxone unit. The drug is likely one reason why the number of fatal drug overdoses have dropped so far this year in Chautauqua County. P-J photo by Eric Tichy

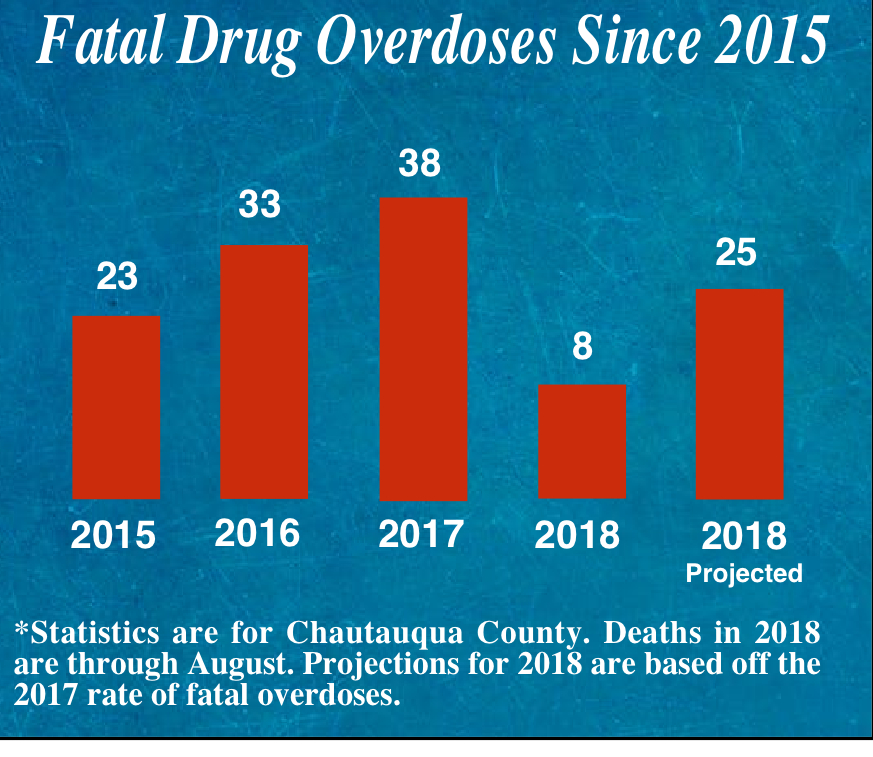

While in the midst of what many have called an opioid epidemic, the 2018 rate of drug overdose deaths has declined by at least 12 percent compared to 2017 in Chautauqua County.

Breeanne Agett, epidemilogy manager at the Chautauqua County Department of Health and Human Services, shared data with The Post-Journal that incidates the decline could be as much as 68 percent for the first eight months of 2018, a figure dependent on how many pending overdose investigations turn into drug-induced fatalities.

Agett attributed the decline of fatal drug overdoses to a variety of likely factors, including an increase in availability and use of naloxone to counter the effects of opioids, a shift in drug use from opioids to methamphetamine and an increase in access to drug treatment and recovery resources.

“It would be difficult to attribute the number of lives saved for each of these factors,” Agett said, “but the truth probably lies somewhere in the middle. Each of these factors likely play a role in the reduction in fatal overdoses that we’re seeing in the community.”

Phil Wilson, operations manager at Alstar EMS, agrees that a multitude of factors is helping tackle the problems of drug and specifically opioid use. He cited more education regarding the dangers of opioid abuse results in an increase sense of caution for some potential users. Training for use of naloxone has also helped prepare citizens who are not first responders to administer the substance nasally to those who may need the effects of opioids reversed.

P-J file photo

“If we assume that drug overdose deaths occur at the same rate in 2018 as in 2017, we would expect about 25 drug overdose deaths by the end of August,” Agett said.

Instead, there have been only eight drug overdose deaths in the county in 2018 as of Sept. 11. There are also 14 pending investigations into drug-related incidents as of that date, but even if all investigations revealed confirmed drug overdose deaths, totaling 22 fatalities, which Agett adds would be a very cautious prediction and unlikely result of the investigations, the decline in overdose deaths would still be 12 percent.

Overall in 2017, there were 42 drug-related deaths and 38 drug overdose deaths in Chautauqua County with one remaining pending investigation. There have been 10 drug-related deaths along with the eight drug overdose deaths and 14 pending investigations so far in 2018.

Drug-related deaths include all overdose deaths as well as deaths that occurred at least partially as a result of chronic or past drug use. Overdose deaths are classified as deaths in which an acute intoxication has been recorded; deaths caused by positional asphyxia due to drug intoxication are counted as overdose deaths. Due to a backlog of cases to complete, the Medical Examiner’s Office in Erie County performs autopsies as needed. Agett stated that, largely due to the opioid epidemic, this explains the current number of pending investigations.

According to toxicology reports, opioids have contributed to the vast amount of overdose deaths in 2017. Of the 42 drug-related deaths, 28 deaths were caused at least in part by polypharmacy, the practice of taking multiple drugs concurrently. The opioid fentanyl, prescribed for controlled use as a pain reliever, was also found in the bodies in half of the total drug-related deaths. Heroin was recorded in 14 cases, and methamphetamine was recorded in six cases.

The crossover of drug use was prevalent in 2017, the worst year for drug-related deaths and overdoses in the past few years in Chautauqua County. A total of 29 drug-related deaths and 23 drug overdose deaths were recorded in 2015, and 36 drug-related deaths and 33 drug overdose deaths were recorded in 2016. Agett said these data points only represent known instances of drug-related deaths and that some deaths involving drugs may not be reported as such.

The health department also doesn’t receive death certificates for county residents who die in other counties, but an electronic system provided by New York State is in the works, so that hospitals and health departments can more easily share death certificates.

Not all drug-related incidents result in overdoses or deaths, however. Wilson estimated that Alstar EMS has responded to 12 to 15 incidents per month in 2017 and eight to ten incidents per month so far in 2018.

“We’d like to not have any of those calls,” said Wilson, who noted that just because there is a decline in drug overdose deaths, that doesn’t mean the problem is solved or it’s time for legislators, first responders or the community to become complacent or indifferent to the issue.

“We aren’t seeing that much (decrease),” said David Thomas, executive director of Alstar EMS, who noted that the need for saving lives is as high as ever. Just because opioid-related fatalities have gone down doesn’t mean overall opioid use has followed suit.

THE ROLE OF NALOXONE

In 2016, 76 patients received Narcan, a brand name for naloxone, which means that the substance was either administered nassaly or via IV 6.3 times per month. These numbers rose to 104 patients receiving Narcan in 2017, equaling an average of 8.7 times per month Narcan was administered. Thomas said the 2018 average per month comes to 8.8, meaning that use of opioids has not seemed to have decreased.

Treatment with naloxone isn’t just a shot in the dark. As of the past year, a nationally used software program called ODMAP has been introduced as a tool in Chautauqua County and is being utilized by first responder agencies including police, fire and EMS services, and county health departments to pinpoint where overdoses are occurring, to better understand the epidemic and to record overdose deaths and use of naloxone more effectively. It can also be used to track non-fatal drug overdoses, and hospital emergency rooms will be assisting in collecting data for the program. ODMAP also assists with federal investigations of where drugs are being transported throughout the country.

“We’ve seen really positive results from (ODMAP),” Wilson said.

Wilson said this online service helps provide law enforcement and EMS with areas in the county they can focus on to combat opioid use. It also may suggest what kinds of training could be better implemented to solve the problems of drug use and overdoses. He also said the service is a great collaboration and the finest example he’s seen of different agencies working together.

“(ODMAP)’s helpful for police agencies because they’re able to see when and where overdoses are occurring,” Agett said. “It’s nice from a prevention and response perspective.”

Narcan use has risen recently in Chautauqua County, with 111 reported administrations in 2015, 89 in 2016, 160 in 2017 and 105 in 2018 (the 2018 number is on track to meet the 2017 number if administrations continue at the same rate) as of Thursday. Due to assistance from a grant, the Southern Tier Health Care System is able to provide Narcan kits to first responders. The partnership with this nonprofit and emergency services in Chautauqua, Allegany and Cattaraugus counties has helped supply replacement Narcan kits after EMS and other first responders report kits are used. Wilson said about half of all kits are now supplied through the Souther Tier Health Care System while the other half are paid for by departments. One Narcan nasal kit costs approximately $80.

Since 2015 in Chautauqua County, the Southern Tier Overdose Prevention Program has provided 365 naloxone kits and trained 279 individuals to use naloxone. These individuals include 122 EMS providers, 36 friends or family members, 97 health service providers, 14 members of law enforcement and 10 school personnel.

The Chautauqua County Department of Health also provides naloxone training and be reached at (866) 604-6789. Donna Kahm, president and CEO of Southern Tier Health Care System, can be called at 372-0614 for more details. Either agency can be contacted by those interested in getting trained to administer naloxone.

“The ability to provide Narcan training and kits to our community members represents one piece of a multi-faceted approach to combating this issue,” Kahm said. “We are extremely lucky to work with several agencies in our community that are all working towards the goal of preventing substance use and supporting access to treatment and recovery services.”

In rare cases, such as when super potent opioids like carfentanyl are used, naloxone may have to be administered more than once. Naloxone can only act as an antagonist to opioids in the body to a limited degree, meaning that a second dose may be needed for an individual who overdosed shortly after the initial treatment. Wilson said that many opioids are dealed in a non-controlled environment, necessitating the need for hospital checkups after naloxone is given.

Those trained to administer naloxone can request it from some pharmacies. It is made available as an over-the-counter substance, but anyone who wants it must ask a pharmacist for it. Some insurances may cover the costs, and doctors can also write a prescription for it.